Breaking News

Palantir kills people? But Who's Really Pushing the Buttons?

Palantir kills people? But Who's Really Pushing the Buttons?

'Big Short' investor Michael Burry sounds alarm on AI bubble that's 'too big to save

'Big Short' investor Michael Burry sounds alarm on AI bubble that's 'too big to save

2026-01-21 -- Ernest Hancock interviews Professor James Corbett (Corbett Report) MP3&4

2026-01-21 -- Ernest Hancock interviews Professor James Corbett (Corbett Report) MP3&4

Joe rogan reacts to the Godfather of Ai Geoffrey Hinton talk of his creation

Joe rogan reacts to the Godfather of Ai Geoffrey Hinton talk of his creation

Top Tech News

The day of the tactical laser weapon arrives

The day of the tactical laser weapon arrives

'ELITE': The Palantir App ICE Uses to Find Neighborhoods to Raid

'ELITE': The Palantir App ICE Uses to Find Neighborhoods to Raid

Solar Just Took a Huge Leap Forward!- CallSun 215 Anti Shade Panel

Solar Just Took a Huge Leap Forward!- CallSun 215 Anti Shade Panel

XAI Grok 4.20 and OpenAI GPT 5.2 Are Solving Significant Previously Unsolved Math Proofs

XAI Grok 4.20 and OpenAI GPT 5.2 Are Solving Significant Previously Unsolved Math Proofs

Watch: World's fastest drone hits 408 mph to reclaim speed record

Watch: World's fastest drone hits 408 mph to reclaim speed record

Ukrainian robot soldier holds off Russian forces by itself in six-week battle

Ukrainian robot soldier holds off Russian forces by itself in six-week battle

NASA announces strongest evidence yet for ancient life on Mars

NASA announces strongest evidence yet for ancient life on Mars

Caltech has successfully demonstrated wireless energy transfer...

Caltech has successfully demonstrated wireless energy transfer...

The TZLA Plasma Files: The Secret Health Sovereignty Tech That Uncle Trump And The CIA Tried To Bury

The TZLA Plasma Files: The Secret Health Sovereignty Tech That Uncle Trump And The CIA Tried To Bury

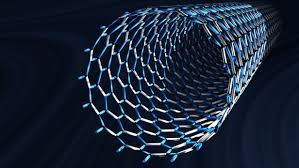

Laser-activated nanotube skin shows where the strain is

Whether they're in airplane wings, bridges or other critical structures, cracks can cause catastrophic failure before they're large enough to be noticed by the human eye. A strain-sensing "skin" applied to such objects could help, though, by lighting up when exposed to laser light.

Developed by a team led by Rice University's Bruce Weisman and Satish Nagarajaiah, the skin is actually a barely-visible very thin film. It consists of a bottom layer of carbon nanotubes dispersed within a polymer, and a top transparent protective layer composed of a different type of polymer (carbon nanotubes are basically microscopic rolled-up sheets of graphene, graphene being a one-atom-thick sheet of linked carbon atoms).

As is the case with carbon nanotubes in general, the ones in the skin fluoresce when subjected to laser light. Depending on how much mechanical strain they're under, however, they'll fluoresce at different wavelengths. Therefore, by analyzing the wavelength of the near-infrared light that the nanotubes are emitting, a handheld reader device can ascertain the amount of strain being exerted on any one area of the skin – and thus on the material underlying it.

The skin has been tested on aluminum bars, which were weakened in one spot with a hole or a notch. While those bars initially appeared uniform to the reader, the skin dramatically indicated where the weakened areas were once the bars were placed under tension.

Nano Nuclear Enters The Asian Market

Nano Nuclear Enters The Asian Market