Breaking News

After Trump Meeting, Slovak PM Fico Says 'EU Is Not Taken Seriously' By World Leaders

After Trump Meeting, Slovak PM Fico Says 'EU Is Not Taken Seriously' By World Leaders

US NatGas Poised For Biggest Weekly Spike On Record As "Blizzard Of '96" Fears Resurfa

US NatGas Poised For Biggest Weekly Spike On Record As "Blizzard Of '96" Fears Resurfa

Police Use Tear Gas, Stun Grenades Against Farmers Protesting Mercosur Trade Agreement At EU...

Police Use Tear Gas, Stun Grenades Against Farmers Protesting Mercosur Trade Agreement At EU...

Supreme Court Seems Skeptical Over Lisa Cook Firing

Supreme Court Seems Skeptical Over Lisa Cook Firing

Top Tech News

The day of the tactical laser weapon arrives

The day of the tactical laser weapon arrives

'ELITE': The Palantir App ICE Uses to Find Neighborhoods to Raid

'ELITE': The Palantir App ICE Uses to Find Neighborhoods to Raid

Solar Just Took a Huge Leap Forward!- CallSun 215 Anti Shade Panel

Solar Just Took a Huge Leap Forward!- CallSun 215 Anti Shade Panel

XAI Grok 4.20 and OpenAI GPT 5.2 Are Solving Significant Previously Unsolved Math Proofs

XAI Grok 4.20 and OpenAI GPT 5.2 Are Solving Significant Previously Unsolved Math Proofs

Watch: World's fastest drone hits 408 mph to reclaim speed record

Watch: World's fastest drone hits 408 mph to reclaim speed record

Ukrainian robot soldier holds off Russian forces by itself in six-week battle

Ukrainian robot soldier holds off Russian forces by itself in six-week battle

NASA announces strongest evidence yet for ancient life on Mars

NASA announces strongest evidence yet for ancient life on Mars

Caltech has successfully demonstrated wireless energy transfer...

Caltech has successfully demonstrated wireless energy transfer...

The TZLA Plasma Files: The Secret Health Sovereignty Tech That Uncle Trump And The CIA Tried To Bury

The TZLA Plasma Files: The Secret Health Sovereignty Tech That Uncle Trump And The CIA Tried To Bury

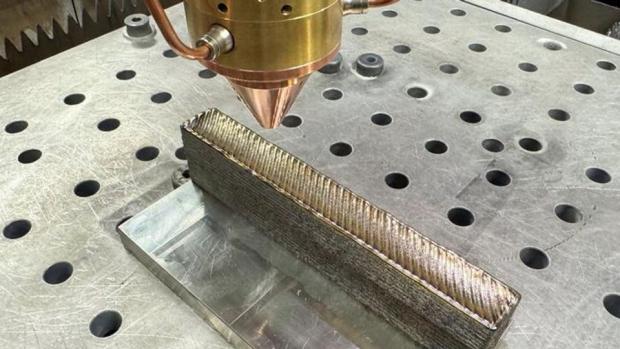

New 3D-printed titanium alloy is stronger and cheaper than ever before

Because they have exceptional strength-to-weight ratios, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility, titanium alloys are used to make aircraft frames, jet engine parts, hip and knee replacements, dental implants, ship hulls, and golf clubs.

Ryan Brooke, an additive manufacturing researcher at Australia's RMIT University, believes we can do way better. "3D printing allows faster, less wasteful and more tailorable production yet we're still relying on legacy alloys like Ti-6Al-4V that doesn't allow full capitalization of this potential," he says. "It's like we've created an airplane and are still just driving it around the streets."

Ti-6Al-4V is also known as Titanium alloy 6-4 or grade 5 titanium, and is a combination of aluminum and vanadium. It's strong, rigid, and highly fatigue resistant. However, 3D-printed Ti-6Al-4V has a propensity for columnar grains, which means that parts made from this material can be strong in one direction but weak or inconsistent in others – and therefore may need alloying with other elements to correct this.

To be fair, Brooke is putting his money where his mouth is. He's authored a paper that appeared in Nature this month on a new approach to finding a reliable way to predict the grain structure of metals made using additive manufacturing, and thereby guide the design of new high-performance alloys we can 3D print.

The researchers' approach, which has been in the works for the last three years, evaluated three key parameters in predicting the grain structure of alloys to determine whether an additive manufacturing recipe would yield a good alloy:

Non-equilibrium solidification range(ΔTs): the temperature range over which the metal solidifies under non-equilibrium conditions.

Growth restriction factor (Q): the initial rate at which constitutional supercooling develops at the very beginning of solidification.

Constitutional supercooling parameter (P): the overall potential for new grains to nucleate and grow throughout the solidification process, rather than just at the very beginning.

Through this work, the team experimentally verified that P is the most reliable parameter for guiding the selection of alloying elements in 3D-printed alloys to achieve desired grain structures for strength and durability.

Nano Nuclear Enters The Asian Market

Nano Nuclear Enters The Asian Market