Breaking News

DRINK 1 CUP Before Bed for a Smaller Waist

Nano-magnets may defeat bone cancer and help you heal

Nano-magnets may defeat bone cancer and help you heal

Dan Bongino Officially Leaves FBI After One-Year Tenure, Says Time at the Bureau Was...

Dan Bongino Officially Leaves FBI After One-Year Tenure, Says Time at the Bureau Was...

WATCH: Maduro Speaks as He's Perp Walked Through DEA Headquarters in New York

WATCH: Maduro Speaks as He's Perp Walked Through DEA Headquarters in New York

Top Tech News

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Methane-Eating Bacteria Converts Greenhouse Gas to Fuel (And Could Clean-up Fracking Sites)

Yet we know very little about how the complex reaction occurs, limiting our ability to use the double benefit to our advantage.

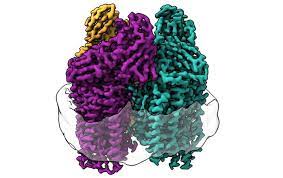

By studying the enzyme the bacteria use to catalyze the reaction, a team at Northwestern University now has discovered key structures that may drive the process.

Their findings ultimately could lead to the development of human-made biological catalysts that convert methane gas into methanol.

"Methane has a very strong bond, so it's pretty remarkable there's an enzyme that can do this," said Northwestern's Amy Rosenzweig, senior author of the paper. "If we don't understand exactly how the enzyme performs this difficult chemistry, we're not going to be able to engineer and optimize it for biotechnological applications."

The enzyme, called particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO), is a particularly difficult protein to study because it's embedded in the cell membrane of the bacteria.