Breaking News

Powerful Pro-life Ad Set to Air During Super Bowl 'Adoption is an Option' (Video)

Powerful Pro-life Ad Set to Air During Super Bowl 'Adoption is an Option' (Video)

Even in Winter, the Sun Still Shines in These Citrus Recipes

Even in Winter, the Sun Still Shines in These Citrus Recipes

Dates: The Ancient Fertility Remedy Modern Medicine Ignores Amid Record Low Birth Rates

Dates: The Ancient Fertility Remedy Modern Medicine Ignores Amid Record Low Birth Rates

Amazon's $200 Billion Spending Shock Reveals Big Tech's Centralization Crisis

Amazon's $200 Billion Spending Shock Reveals Big Tech's Centralization Crisis

Top Tech News

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

"Tiny skyscraper" electrodes boost bioenergy output of blue-green algae

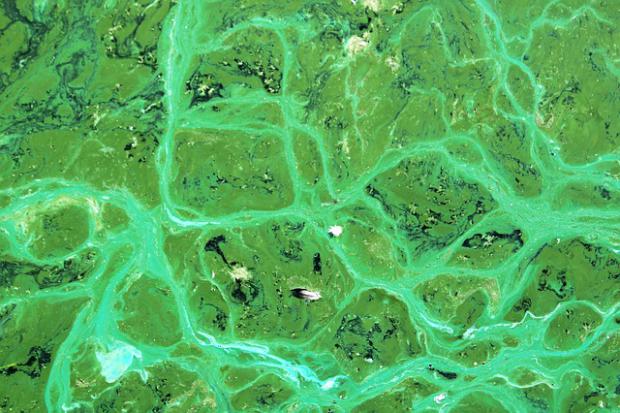

These tiny grids of "nano-housing" create the optimal environment to not just foster the rapid growth of these bacteria, but take their energy-harvesting potential to new heights.

Also known as cyanobacteria or perhaps more familiarly, blue-green algae, photosynthetic bacteria can be found in all types of water, where they use sunlight to make their own food. Their natural proficiency at this task has inspired many promising avenues of research into renewable energy, from bionic mushrooms that generate electricity, to algae-fueled bioreactors that soak up carbon dioxide, to self-contained solutions that offer a blueprint for commercial artificial photosynthesis systems.

Cyanobacteria thrive in environments like lake surfaces as they require lots of sunlight to grow, and a team at the University of Cambridge has made a breakthrough that came about by experimenting with ways to better satisfy these needs. Another thing for the team to consider was that to gather any of the energy they produce through photosynthesis, the bacteria need to be attached to electrodes. By crafting electrodes that also promote the growth of the bacteria, the scientists are effectively trying to kill two birds with one stone.

"There's been a bottleneck in terms of how much energy you can actually extract from photosynthetic systems, but no one understood where the bottleneck was," said Dr Jenny Zhang, who led the research. "Most scientists assumed that the bottleneck was on the biological side, in the bacteria, but we've found that a substantial bottleneck is actually on the material side."

Smart dust technology...

Smart dust technology...