Breaking News

Powerful Pro-life Ad Set to Air During Super Bowl 'Adoption is an Option' (Video)

Powerful Pro-life Ad Set to Air During Super Bowl 'Adoption is an Option' (Video)

Even in Winter, the Sun Still Shines in These Citrus Recipes

Even in Winter, the Sun Still Shines in These Citrus Recipes

Dates: The Ancient Fertility Remedy Modern Medicine Ignores Amid Record Low Birth Rates

Dates: The Ancient Fertility Remedy Modern Medicine Ignores Amid Record Low Birth Rates

Amazon's $200 Billion Spending Shock Reveals Big Tech's Centralization Crisis

Amazon's $200 Billion Spending Shock Reveals Big Tech's Centralization Crisis

Top Tech News

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

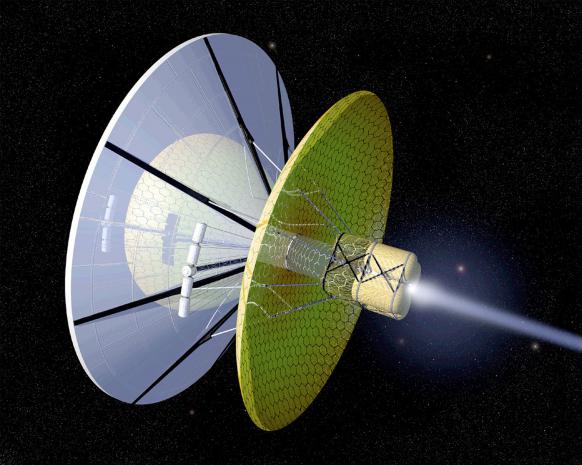

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

Science fiction revisited: Ramjet propulsion

In science fiction stories about contact with extraterrestrial civilisations, there is a problem: What kind of propulsion system could make it possible to bridge the enormous distances between the stars? It cannot be done with ordinary rockets like those used to travel to the moon or Mars. Many more or less speculative ideas about this have been put forward—one of them is the "Bussard collector" or "Ramjet propulsion". It involves capturing protons in interstellar space and then using them for a nuclear fusion reactor.

Peter Schattschneider, physicist and science fiction author, has now analyzed this concept in more detail together with his colleague Albert Jackson from the USA. The result is unfortunately disappointing for fans of interstellar travel: it cannot work the way Robert Bussard, the inventor of this propulsion system, thought it up in 1960. The analysis has now been published in the scientific journal Acta Astronautica.

The hydrogen-collecting machine

"The idea is definitely worth investigating," says Prof. Peter Schattschneider. "In interstellar space there is highly diluted gas, mainly hydrogen—about one atom per cubic centimeter. If you were to collect the hydrogen in front of the spacecraft, like in a magnetic funnel, with the help of huge magnetic fields, you could use it to run a fusion reactor and accelerate the spacecraft." In 1960, Robert Bussard published a scientific paper about this. Nine years later, such a magnetic field was described theoretically for the first time. "Since then, the idea has not only excited science fiction fans, but has also generated a great deal of interest in the technical and scientific astronautics community," says Peter Schattschneider.

Peter Schattschneider and Albert Jackson now took a closer look at the equations, half a century later. Software developed at TU Wien as part of a research project for calculating electromagnetic fields in electron microscopy unexpectedly turned out to be extremely helpful: the physicists were able to use it to show that the basic principle of magnetic particle trapping actually works. Particles can be collected in the proposed magnetic field and guided into a fusion reactor. In this way, considerable acceleration can be achieved—up to relativistic speeds.

Smart dust technology...

Smart dust technology...