Breaking News

Trump has pros as well as cons

Trump has pros as well as cons

Congress To Have Access to Unredacted Epstein Files

Congress To Have Access to Unredacted Epstein Files

How $30BILLION of taxpayers' money put aside for welfare pot became a 'slush fund'...

How $30BILLION of taxpayers' money put aside for welfare pot became a 'slush fund'...

Why This Crash Is Bitcoin's Biggest Test Yet

Why This Crash Is Bitcoin's Biggest Test Yet

Top Tech News

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

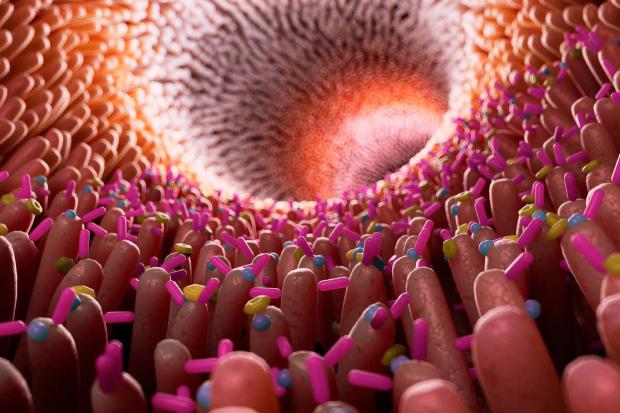

Fermented vs. high-fiber diet microbiome study delivers surprising results

Investigating the relationship between diet, gut bacteria and systemic inflammation, a team of Stanford University researchers has found just a few weeks of following a diet rich in fermented foods can lead to improvements in microbiome diversity and reductions in inflammatory biomarkers.

The new research pitted a high-fiber diet against a diet with lots of fermented food. Thirty-six healthy adults were recruited and randomly assigned one of the two diets for 10 weeks.

"We wanted to conduct a proof-of-concept study that could test whether microbiota-targeted food could be an avenue for combatting the overwhelming rise in chronic inflammatory diseases," explains Christopher Gardner, co-senior author on the new study.

Blood and stool samples were collected before, during, and after the dietary intervention. Over the course of the trial the researchers saw levels of 19 inflammatory proteins drop in the fermented food cohort. This was alongside increases in microbial diversity in the gut and reduced activity in four types of immune cells.

Perhaps most significantly, these changes were not detected in the group tasked with eating a high-fiber diet. Erica Sonnenburg, another co-senior author on the study, says this discordancy between the two cohorts was unexpected.

"We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity," she says. "The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity."

Smart dust technology...

Smart dust technology...