Breaking News

Sunday FULL SHOW: Newly Released & Verified Epstein Files Confirm Globalists Engaged...

Sunday FULL SHOW: Newly Released & Verified Epstein Files Confirm Globalists Engaged...

Fans Bash Bad Bunny's 'Boring' Super Bowl Halftime Show, Slam Spanish Language Performan

Fans Bash Bad Bunny's 'Boring' Super Bowl Halftime Show, Slam Spanish Language Performan

Trump Admin Refuses To Comply With Immigration Court Order

Trump Admin Refuses To Comply With Immigration Court Order

U.S. Government Takes Control of $400M in Bitcoin, Assets Tied to Helix Mixer

U.S. Government Takes Control of $400M in Bitcoin, Assets Tied to Helix Mixer

Top Tech News

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

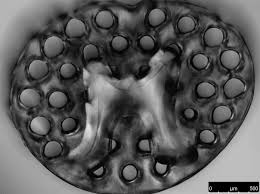

3D Printed Bioimplants Repaired Spinal Cords and Restored Motor Function

The implants are hydrogel structures that can be rapidly 3D printed into different sizes and shapes, making them easily customizable to fit the precise anatomy of a patient's spinal cord injury. Researchers fill the implants with neural stem cells and then they are fitted, like missing puzzle pieces, into sites of spinal cord injury. New nerve cells grow and axons—long, hair-like extensions through which nerve cells pass signals to other nerve cells—regenerate, allowing new nerve cells to connect with each other and the host spinal cord tissue.

"Using our rapid 3D printing technology, we've created a scaffold that mimics central nervous system structures. Like a bridge, it aligns regenerating axons from one end of the spinal cord injury to the other. Axons by themselves can diffuse and regrow in any direction, but the scaffold keeps axons in order, guiding them to grow in the right direction to complete the spinal cord connection," said co-senior author Shaochen Chen, professor of nanoengineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and faculty member of the Institute of Engineering in Medicine at UC San Diego.

"In recent years and papers, we've progressively moved closer to the goal of abundant, long-distance regeneration of injured axons in spinal cord injury, which is fundamental to any true restoration of physical function," said Tuszynski.

Smart dust technology...

Smart dust technology...