Breaking News

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Top Tech News

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

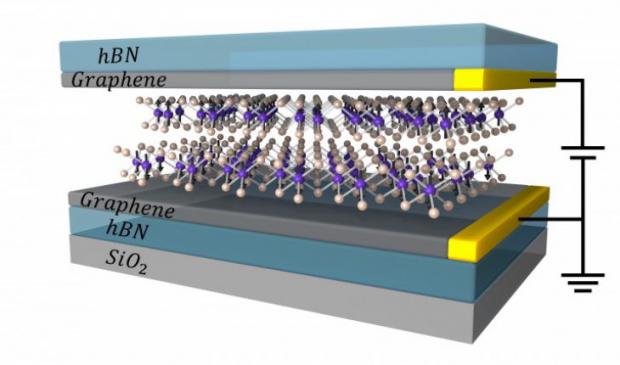

Atom thin magnetic memory

Researchers report that they used stacks of ultrathin materials to exert unprecedented control over the flow of electrons based on the direction of their spins — where the electron "spins" are analogous to tiny, subatomic magnets. The materials that they used include sheets of chromium tri-iodide (CrI3), a material described in 2017 as the first ever 2-D magnetic insulator. Four sheets — each only atoms thick — created the thinnest system yet that can block electrons based on their spins while exerting more than 10 times stronger control than other methods.

"Our work reveals the possibility to push information storage based on magnetic technologies to the atomically thin limit," said co-lead author Tiancheng Song, a UW doctoral student in physics.

Science – Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in spin-filter van der Waals heterostructures

With up to four layers of CrI3, the team discovered the potential for "multi-bit" information storage. In two layers of CrI3, the spins between each layer are either aligned in the same direction or opposite directions, leading to two different rates that the electrons can flow through the magnetic gate. But with three and four layers, there are more combinations for spins between each layer, leading to multiple, distinct rates at which the electrons can flow through the magnetic material from one graphene sheet to the other.

"Instead of your computer having just two choices to store a piece of data in, it can have a choice A, B, C, even D and beyond," said co-author Bevin Huang, a UW doctoral student in physics. "So not only would storage devices using CrI3 junctions be more efficient, but they would intrinsically store more data."