Breaking News

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Top Tech News

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

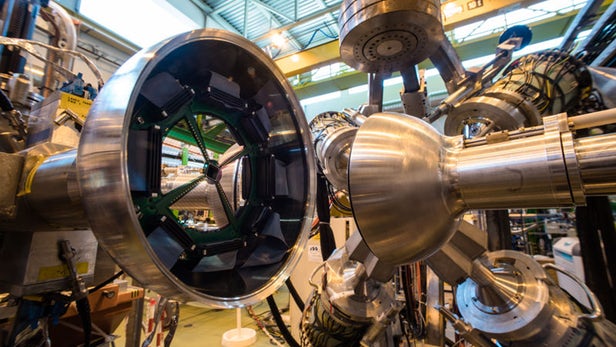

CERN scientists get antimatter ready for its first road trip

Antimatter is notoriously tricky to store and study, thanks to the fact that it will vanish in a burst of energy if it so much as touches regular matter. The CERN lab is one of the only places in the world that can readily produce the stuff, but getting it into the hands of the scientists who want to study it is another matter (pun not intended). After all, how can you transport something that will annihilate any physical container you place it in? Now, CERN researchers are planning to trap and truck antimatter from one facility to another.

Antimatter is basically the evil twin of normal matter. Each antimatter particle is identical to its ordinary counterpart in almost every way, except it carries the opposite charge, leading the two to destroy each other if they come into contact. Neutron stars and jets of plasma from black holes may be natural sources, and it even seems to be formed in the Earth's atmosphere with every bolt of lightning.

Studying antimatter could help us unlock some of the Universe's most profound mysteries – but, of course, the Universe isn't giving up those answers easily. Positrons (or anti-electrons) were the first antimatter particles to be observed in experiments in the 1930s, and like regular matter, these antiparticles clump together to form atoms of antimatter.

Antihydrogen atoms were first created at CERN in 1995, but it wasn't until 2010 that scientists managed to trap and study them properly – even if only for fractions of a second. In 2011, researchers managed to hold onto the antimatter atoms for a solid 16 minutes, allowing them to eventually study their spectra to see how they compare to regular old hydrogen.

Nowadays, CERN can readily produce antiprotons in a particle decelerator, slowing them down to be captured in a specially-designed trap. But to really make the most of them, it's time for the volatile substance to leave the nest, and be put to work in other areas of research.