Breaking News

No clear Iran endgame as Trump's position shifts by the hour

No clear Iran endgame as Trump's position shifts by the hour

US-Israel Iran War Live Updates: US Navy has not escorted any tankers through Strait of Hormuz...

US-Israel Iran War Live Updates: US Navy has not escorted any tankers through Strait of Hormuz...

Scott Ritter: Iran HITTING US BASES & ISRAEL LIKE NEVER BEFORE, Trump's Oil War Backfires

Scott Ritter: Iran HITTING US BASES & ISRAEL LIKE NEVER BEFORE, Trump's Oil War Backfires

Top Tech News

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

New metallic glass material created by starving atoms of a nucleus

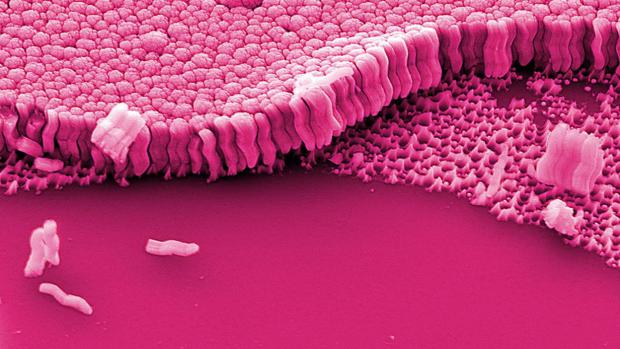

Normally, solid metals have a rigid, crystalline atomic structure, but as their name suggests, metallic glasses are more like glass, with a random arrangement of atoms. Composed of complex alloys, they get their unusual structure when molten metal is cooled down extremely quickly, which prevents crystals from forming. The end result is a material that's as pliable as plastic during production but strong as steel afterwards, making them useful for objects like golf clubs and gears for robots.

The Yale researchers developed their new version of the material by taking samples of metallic glass and making nanorods out of it. With a diameter of just 35 nanometers, these rods are so tiny that the atoms have no room for a nucleus. The researchers dub the process "nucleus starvation," and it resulted in a new phase of the material.

"This gives us a handle to control the number of nuclei we provide in the sample," says Judy Cha, lead researcher on the project. "When it doesn't have any nuclei — despite the fact that nature tells us that there should be one — it generates this brand new crystalline phase that we've never seen before. It's a way to create a new material out of the old."

X BANS AI War Videos

X BANS AI War Videos