Breaking News

No clear Iran endgame as Trump's position shifts by the hour

No clear Iran endgame as Trump's position shifts by the hour

US-Israel Iran War Live Updates: US Navy has not escorted any tankers through Strait of Hormuz...

US-Israel Iran War Live Updates: US Navy has not escorted any tankers through Strait of Hormuz...

Scott Ritter: Iran HITTING US BASES & ISRAEL LIKE NEVER BEFORE, Trump's Oil War Backfires

Scott Ritter: Iran HITTING US BASES & ISRAEL LIKE NEVER BEFORE, Trump's Oil War Backfires

Top Tech News

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

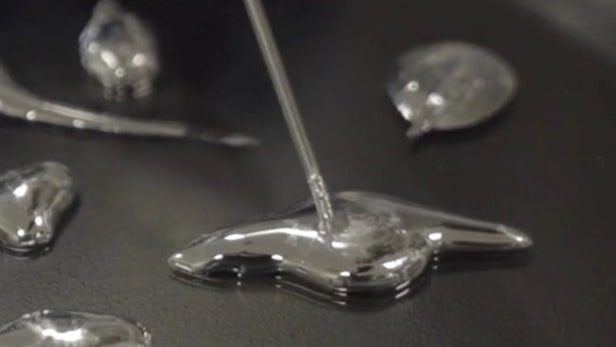

Transistor breakthrough brings liquid computers closer to reality

In a step towards creating a new class of electronics that look and feel like soft, natural organisms, mechanical engineers at Carnegie Mellon University are developing a fluidic transistor out of a metal alloy of indium and gallium that is liquid at room temperature. From biocompatible disease monitors to shape-shifting robots, the potential applications for such squishy computers are intriguing.

Until recently, the only example of liquid electronics were microswitches made up of tiny glass tubes with a bead of mercury inside that closes the switch when it rolls between two wires. Essentially, the fluidic transistor is a much more sophisticated switch that's made of a liquid metal alloy that is non-toxic, so it can be infused into rubber to create soft, stretchable circuits.

Unlike the mercury switch, where tilting the vial closes the circuit, the fluidic transistor works by opening and closing the connection between metal droplets using the direction of the voltage. When it flows in one direction, the droplets combine and the circuit closes. If it flows the other way, the droplet splits and the circuit opens.

Researchers Carmel Majidi and James Wissman of the Soft Machines Lab at Carnegie Mellon say that alternating the opening and closing of the switch allows it to mimic a transistor, thanks to the phenomenon of capillary instability. The hard part was getting inducing the instability so the droplets change from two to one and back seamlessly.

"We see capillary instabilities all the time," says Majidi. "If you turn on a faucet and the flow rate is really low, sometimes you'll see this transition from a steady stream to individual droplets. That's called a Rayleigh instability."

By testing the droplets in a sodium hydroxide bath the engineers found that there was a relationship between the voltage and an electrochemical reaction where voltage produced a gradient in the oxidation on the droplet's surface, altering the surface tension and causing the droplet to split in two. More important, the properties of the switch acted like a transistor.

X BANS AI War Videos

X BANS AI War Videos