Breaking News

After Trump's War, the US Military Won't Be Invited Back

After Trump's War, the US Military Won't Be Invited Back

US Will Take and Keep Kharg Island Before War is Over

US Will Take and Keep Kharg Island Before War is Over

Counterterrorism/Military Expert Warns That President Trump Is Walking Into A Deep State Trap...

Counterterrorism/Military Expert Warns That President Trump Is Walking Into A Deep State Trap...

The US Military Is Involved In A Massive Mobilization Of Infantry Troops To Launch A FULL SCALE...

The US Military Is Involved In A Massive Mobilization Of Infantry Troops To Launch A FULL SCALE...

Top Tech News

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

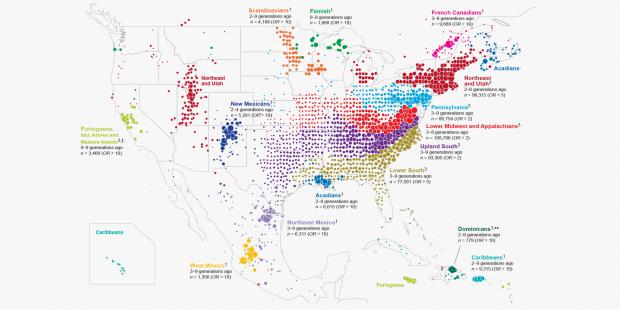

770,000 Tubes of Spit Help Map America's Great Migrations

Using more than 770,000 spit samples taken from their customers over the last five years, its researchers mapped how people moved and married in post-colonial America. And their choices—especially the ones that kept communities apart—shaped today's modern genetic landscape.

The study, published today in Nature Communications, combines a DNA database with family tree information collected over the company's 34-year history. "We're all living under the assumption that we are individual agents," says Catherine Ball, chief scientific officer at Ancestry and the leader of the study. "But people actually are living in the course of history." And from the moment they spit, send, and consent, DNA kit customers become actors in a much larger story—told through the massive data sets companies like Ancestry are accumulating from casual genealogists.

Ball's team of geneticists and statisticians started by pulling out subsets of closely related people from their 770,000 spit samples. In that analysis, each person appears as a dot, while their genetic relationships to everyone else in the database are sticks. The result, Ball says, "looks like a giant hairball."

From that hairball her team pulled out more than 60 unique genetic communities—Germans in Iowa and Mennonites in Kansas and Irish Catholics on the Eastern seaboard. Then they mined their way through generations of family trees (also provided by their customers) to build a migratory map. Finally, they paired up with a Harvard historian to understand why communities moved and dispersed the ways they did. Religion and race were powerful deterrents to gene flow. But nothing, it turned out, was stronger than the Mason Dixon line.