Breaking News

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Top Tech News

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

Process for producing ammonia that generates electricity instead of consuming energy...

Nearly a century ago, German chemist Fritz Haber won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for a process to generate ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen gases. The process, still in use today, ushered in a revolution in agriculture, but now consumes around one percent of the world's energy to achieve the high pressures and temperatures that drive the chemical reactions to produce ammonia.

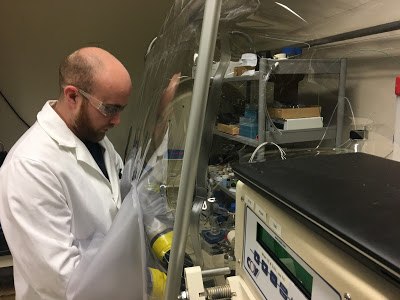

Today, University of Utah chemists publish a different method, using enzymes derived from nature, that generates ammonia at room temperature. As a bonus, the reaction generates a small electrical current.

Although chemistry and materials science and engineering professor Shelley Minteer and postdoctoral scholar Ross Milton have only been able to produce small quantities of ammonia so far, their method could lead to a less energy-intensive source of the ammonia, used worldwide as a vital fertilizer.