Breaking News

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

The Pentagon Failed Its Audit Again. You Should Be Alarmed.

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Cuban Crisis 2.0. What if 'Gerans' flew from Cuba?

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Senate Democrats Offer Promising Ideas for Changing Immigration Enforcement

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Never Seen Risk Like This Before in My Career

Top Tech News

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

Lab–grown LIFE takes a major step forward – as scientists use AI to create a virus never seen be

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

New Electric 'Donut Motor' Makes 856 HP but Weighs Just 88 Pounds

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

Donut Lab Says It Cracked Solid-State Batteries. Experts Have Questions.

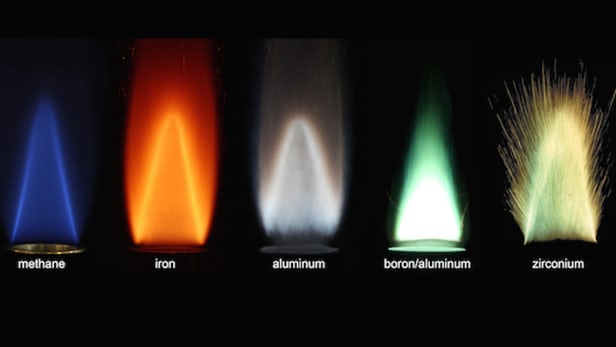

Metal makes for a promising alternative to fossil fuels

The team is studying the combustion characteristics of metal powders to determine whether such powders could provide a cleaner, more viable alternative to fossil fuels than hydrogen, biofuels, or electric batteries.

Metals may seem about as unburnable as it's possible to be, but when ground into extremely fine powder like flour or icing sugar, it's a different story. The simile is an apt one because the metal powders are similar to flour or sugar in more than particle size. Almost anything ground so fine will burn or even explode under the right conditions.

Grinding a powder so fine vastly increases the ratio between the surface area and the volume of the grains, so they burn very readily. In fact, they burn so readily that it's the reason why flour mills are so well ventilated. The slightest spark in floury air and a mill can blow up like a munitions dump. The same goes for sugar, metals, or even some types of rock.

This fact is already employed in a number of areas. Iron or aluminum, for example, can be ground up and turned into colorants for fireworks, solid rocket fuel powerful enough to lift a payload into orbit, or thermite that can burn hot enough to cut steel rails. What the McGill team hopes to do is harness this principle and turn it into a practical power source for everyday use.